Paul MellyWest Africa analyst

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesSpain is kicking against the prevailing political mood among Western nations when it comes to migration and policies regarding the African continent.

At a time when the US, the UK, France and Germany are all cutting back their development aid budgets, Madrid remains committed to continued expansion, albeit from a lower starting point.

This week, the Spanish capital has been hosting an African Union-backed “world conference on people of African descent”. AfroMadrid2025 will discuss restorative justice and the creation of a new development fund.

It is just the latest sign of how Spain’s socialist-led government is seeking to deepen and diversify its engagement with the continent and near neighbour that lies just a few kilometres to the south, across the Straits of Gibraltar.

In July Foreign Minister José Manuel Albares launched a new advisory council of prominent intellectual, diplomatic and cultural figures, more than half of them African, to monitor the delivery of the detailed Spain-Africa strategy that his government published at the end of last year.

New embassies south of the Sahara, and partnerships in business and education are planned.

The contrast between Spain’s approach and that of others in the West is not just in spending but in tone and mindset – and nowhere more so than in dealing with migration.

Similar to elsewhere in Europe, Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez is looking for ways to contain the influx of irregular arrivals.

Like other centre-left and centre-right leaders, he finds himself facing an electoral challenge from the radical right, largely driven by some voters’ concern over migration, with the hardline Vox party well established in parliament and routinely ranking third in opinion polls.

In July, extra security forces had to be deployed against racist thugs roaming the streets of Torre Pacheco, in Murcia region – where many Africans work in the booming horticultural sector – after three Moroccans were accused of beating a pensioner.

While the opposition conservative People’s Party remains favourable to some immigration, but for cultural reasons wants to prioritise Latin Americans rather than Africans, Vox has been more radical.

Responding to the Murcia incident Vox called for a crackdown on immigrants taking up less skilled jobs. The message largely targeted Africans working in fruit and vegetable production, now so crucial to the southern Spanish economy.

But for the government the migration presents challenges that are as much practical as political.

AFP via Getty Images

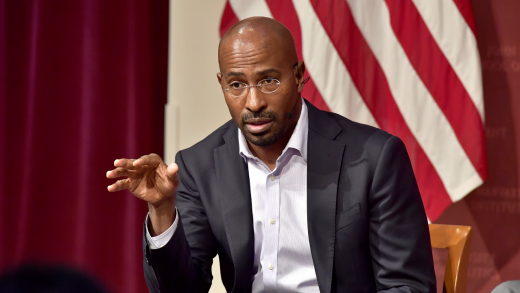

AFP via Getty ImagesMore than 45,000 people made the perilous sea crossing from Africa’s west coast to the Spanish archipelago of the Canary Islands last year. Estimates of those who died while making the attempt range between 1,400 and a staggering 10,460.

Others make the shorter journey across the Gibraltar Straits or the Mediterranean to land on Andalusian beaches or try to scramble over the border fences of Ceuta and Melilla, the two Spanish enclave towns on the North African coast.

The Spanish administration has to accommodate new arrivals, process their claims and manage their absorption into wider society, whether temporary or more long-lasting.

However, in language markedly different from the hostile messaging that emanates from many European capitals, the Sanchez government openly acknowledges the hard economic realities on the ground in West Africa that push people to risk their lives in the effort to reach Europe.

And it is trying to move beyond simply saying “no” to new arrivals. Instead, it is developing creative alternatives, with a promise to foster movements of people that are safe, orderly and regular and “mutually beneficial”.

On his trip to Mauritania last year, Sanchez stressed the contribution that migrants make to the Spanish economy.

“For us, the migratory phenomenon is not only a question of moral principles, solidarity and dignity, but also one of rationality,” the prime minister said.

The Spanish government funds training schemes for unemployed youth in countries such as Senegal, especially for irregular migrants who have been sent back, to help them develop viable new livelihoods back home.

And it has expanded a “circular migration” programme that gives West Africans short-term visas to come to Spain for limited periods of seasonal work, mainly in agriculture, and then return.

These issues were at the heart of the agenda when Sanchez visited Senegal, The Gambia and Mauritania in August last year.

A circular migration agreement with the former had been in place since 2021, but similar accords with the Mauritanian and Gambian governments have since followed.

The underlying case for this singular approach was set out in detail in the foreign ministry’s Spain-Africa strategy. This argued that Europe and Africa “form part of the same geopolitical space”.

But the management of migration is only one motive for the Spanish decision to place emphasis on building relations with Africa – and indeed support a much broader related social-cultural agenda.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThe fundamental premise underlying Madrid’s outreach is that Spain, as the European country closest to the continent, has an essential self interest in Africa’s progress towards inclusive and sustainable development, and peace and security.

That basic rationale might seem obvious.

Yet of course history had taken Spain down a quite different path.

Other than a few Maghreb footholds and a small tropical outpost – today’s independent Equatorial Guinea – its colonial expansion in the 16th and 17th Centuries had mainly been directed across the Atlantic.

And over recent decades, European affairs and the Middle East had tended to dominate Madrid’s foreign policy priorities, while the main beneficiaries of its development support were the countries of its vast former empire in Central and South America.

However, the past few years have seen the Sanchez government preside over a fundamental broadening of outlook.

Barely had Albares been installed as foreign minister in July 2021 than he launched a restructuring of his department, in part to strengthen its engagement not only with Latin America but also with the Sahel and North Africa.

Confirmation of the wider geographical emphasis came with a development co-operation plan for 2024-27, which for the first time, designated West Africa, including the Sahel, as one of three regions prioritised for assistance, alongside Central and South America.

Spain’s Africa strategy lays heavy emphasis not just on economic sectors such as infrastructure, digitalisation and energy transition but also particularly on education and youth employment.

The cultural dimension includes not only promotion of the Spanish language, with an expanded presence of the Cervantes Institute, but also programmes to help the mobility of academic teachers and researchers.

Security co-operation, action on climate change, women’s empowerment and an expanded diplomatic presence are unsurprising components in today’s environment.

However, the strategy also lays very public stress it places on supporting democratic ideas, the African Union and, in particular, the West African regional organisation Ecowas.

This will be welcome public encouragement for the latter, which is currently under severe pressure after seeing its 50th anniversary year marred by the walk-out of the Sahelian states – Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – whose ruling military juntas have refused to comply with its protocol on democracy and good governance.

Meanwhile, in a message targeted as much at Madrid’s domestic audience as its sub-Saharan partners, the foreign ministry said “supporting the African diaspora and the fight against racism and xenophobia are also key priorities”.

Fine words of course are only a first step. But in today’s sour international climate such language really does stand out.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the Africa Programme at Chatham House in London.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC