Back when Barcelona were redefining the way the sport was played at the highest level in the early 2010s, their manager attempted to explain his team’s approach in what seemed like political terms.

“We play leftist football,” Pep Guardiola said.

But it wasn’t that he was using tiki taka to make the case for the Green New Deal or universal health care. (That would be ironic, given how Guardiola and a number of his players got in trouble for not paying their taxes.) Rather, he was trying to verbalize what made his team so different from their competitors: “Everyone does everything.”

His goalkeeper was one of his best passers. His wingers defended like defensive midfielders. His defensive midfielders had the close control of classical attacking midfielders. His attacking midfielders scored lots of goals. His strikers facilitated the central runs of his wingers. The ball was always Barcelona’s because everyone felt comfortable with it, no matter where they were on the field. This was Guardiola Ball.

It certainly was at one time — but it isn’t anymore. After four years of stylistic compromise, it sure seems like Guardiola’s Manchester City have finally become Erling Haaland’s team. When the gigantic, one-dimensional, goal-scoring Norwegian first signed with City back in the summer of 2022, there at least existed the possibility that the then-22-year-old would eventually learn how to be a more active participant in Guardiola’s preferred, constantly shifting possession machine.

If anything, though, it’s gone in the other direction. So far this season, Haaland only does one thing, and then everyone else does all the other things. Manchester City have become a one-man team in a way that would’ve been unthinkable to anyone watching Barcelona back in 2010. But it’s not only that — they’ve become a one-man team in a way we haven’t really seen from any team since 2010.

With 11 goals through eight matches in the Premier League and Champions League, it’s working for Haaland — but can it work for Manchester City?

– O’Hanlon: Re-evaluating this summer’s signings

– First-month grades for all 20 Premier League teams

– Are Man City ‘back’? Not even Pep knows

Why Haaland is better than ever before

Through six games in the Premier League, Haaland is currently averaging 1.42 goals per 90 minutes.

One way to contextualize that: Only six Premier League clubs — Liverpool, Arsenal, Chelsea, Tottenham, Brentford, and Brighton — are averaging more goals per 90 minutes than Haaland.

Another way: When Haaland broke the Premier League goal-scoring record three seasons ago, he averaged a measly 1.17 goals per 90 minutes. His career average at City is 0.98, while his average at Borussia Dortmund was 1.04.

The only numbers that really compare to what he’s doing right now are the ones he put up in his half-season with FC Salzburg in Austria. He averaged 1.47 goals per 90 minutes, but that was for a dominant team that scored 110 goals in a league where no one else got more than 69. He’s doing it today, in the most competitive soccer league in the world.

And, well, he might even be a little better with City than he was with Salzburg. He’s posted the gaudy goal-scoring numbers this season without even attempting a single penalty. Strip out the penalties, and his Salzburg numbers drop down to 1.38.

In fact, just one player in the modern history of the sport has scored non-penalty goals at a higher rate than Haaland is. Among players to feature in at least 500 league minutes across Europe’s Big Five top leagues since the early 1990s, Lionel Messi’s 2012-13 season — when he scored 42 non-penalty goals for Barcelona — is the only one better than Haaland’s rate through the first six games of this season. And it’s just barely better: 1.43 per 90 minutes.

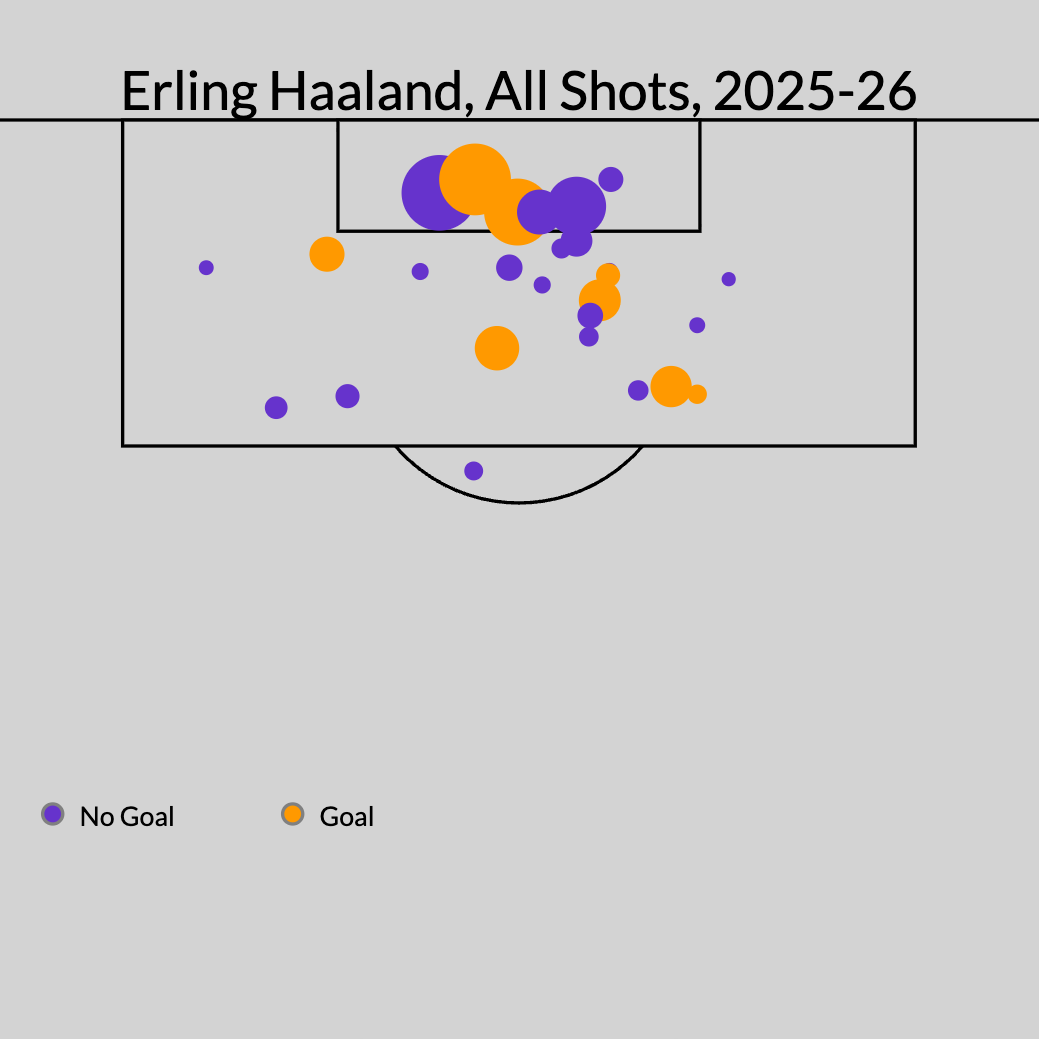

Normally, you can only get to goal-scoring numbers like this with some really hot finishing, but that’s not even happening. No — though six games, Haaland has become the closest thing we’ve seen to a perfect goal-scorer. Take a look at this shot map: the bigger the circle, the higher the expected goals, or xG, value:

Haaland is attempting 4.98 shots per 90 minutes, and the average xG value of his shots is 0.28. Both of those numbers are career highs. That’s not supposed to happen! To take more shots, you have to add some worse, long-range attempts to your repertoire. And to increase your shot quality, you have to subtract shots — stop shooting from deep and just hunt out tap-ins toward the center of the goal.

Or so we thought.

Since the 2017-18 season, 167 players across the Big Five leagues have played at least five full matches worth of minutes and generated an xG per shot number of 0.25 or better. The majority of these players are defenders who barely shot at all but got one tap-in from a goal-mouth scramble or bench strikers who only played later in games, when it’s easier to score goals.

Despite all of that, Haaland’s five shots-per-90 are a full shot more than anyone else in that subset. And if we only look at players who played a similar minutes share to Haaland’s, then the next best is Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang’s 3.0 shots-per-90 for Dortmund and Arsenal in 2017-18.

Flip it around, and it’s just as stark. Only 24 players with significant playing time have averaged at least 5 shots per 90 minutes since 2017-8, and most of them are attacking midfielders on bad teams or the best attackers of the past 20 years: Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, Harry Kane, Kylian Mbappé, Ousmane Dembélé, and others. The best shot-quality after Haaland’s? Robert Lewandowski’s 0.19 xG per shot for Bayern Munich in 2017-8.

All in all, Haaland currently has attempted 28 shots worth 7.5 non-penalty xG that have led to eight goals. Across the rest of the Premier League, the next-best marks are 16, 2.8, and 4.

The modern Premier League history of the one-man team

Through six league games, Manchester City have generated 11.41 non-penalty expected goals — nearly a goal’s worth of chances more than second-best Crystal Palace (10.6). On the whole, City have been a more dangerous attacking team than anyone else in England.

But what that also means is that Haaland has generated 65.5% of the xG for himself. Nearly two-thirds of City’s overall goal-scoring opportunities have fallen to the feet or head of one player. Going back to the 2009-10 season, the previous high for xG share among Premier League players was 45.4%.

It’s also true for shots, albeit to a lesser degree. Haaland has taken 37% of all of City’s shots so far this season — the Premier League’s season-long record since 2009-10 is 32.3%.

1:28

Guardiola reacts to Haaland’s double vs. Burnley: ‘It’s his job’

Pep Guardiola reflects on Manchester City’s comfortable 5-1 win over Burnley in the Premier League.

And so, while we have seen teams rely on a single player for a similar chunk of their shot-generation before, we’ve never seen anyone in the Premier League come close to generating a higher share of the much more important number: the combined quantity and quality of those shots.

The same idea holds true once we go beyond England, too. In the 2010-11 season, Ronaldo actually bested Haaland’s current shot share: he took 39.1% of Real Madrid’s shots. Ronaldo has four other seasons of 34% or more of Madrid’s shot share, and then he did it for Juventus in 2019-20. Messi also broke the 34% barrier four times for Barcelona. No other player for any other team has done it even once.

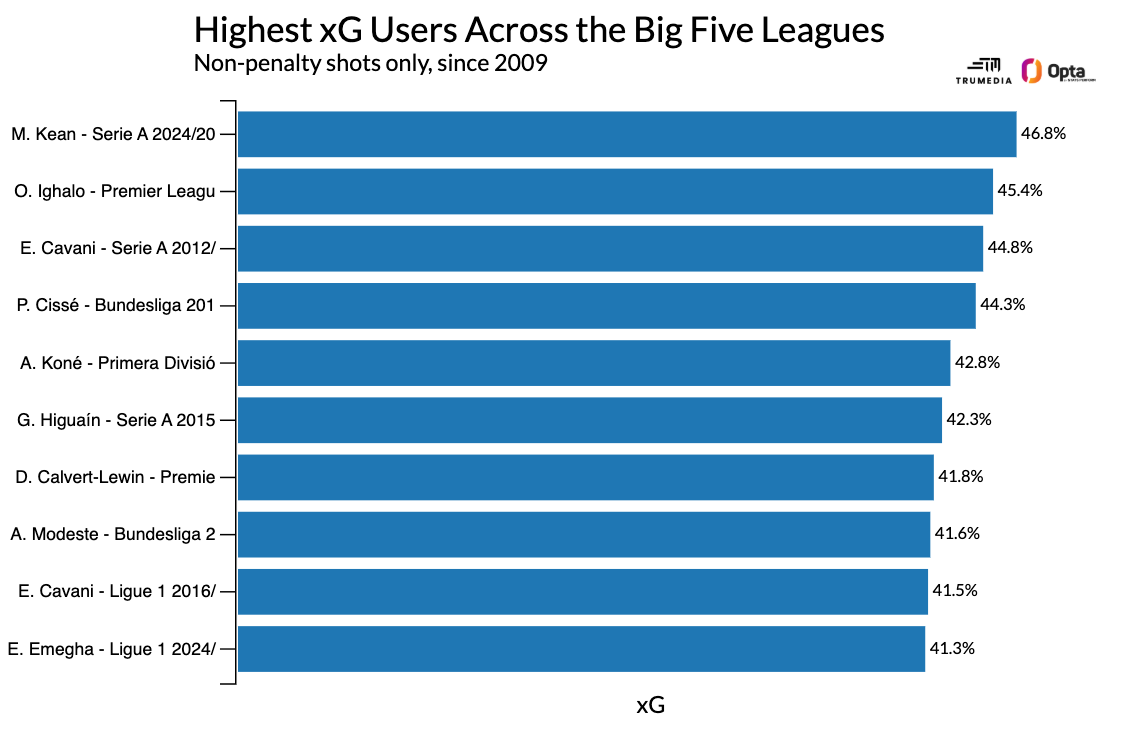

But again, that’s just shots. Once we account for the quality of those shots, Haaland’s current rate stands alone. The next-highest share actually happened last season: Moise Kean’s 46.8% of the xG for Fiorentina. And here’s the top 10 for full-season xG hoarders across the Big Five leagues since 2009:

Let’s quickly run through those players and their teams:

• Moise Kean, Fiorentina, 2024-25: finished sixth in Serie A, qualified for Conference League

• Odion Ighalo, Watford, 2015-16: finished 13th in the Premier League

• Edinson Cavani, Napoli, 2012-13: finished second in Serie A, nine points back of first

• Papiss Cisse, Freiburg, 2010-11: finished ninth in the Bundesliga

• Arouna Kone, Levante, 2011-12: finished sixth in LaLiga

• Gonzalo Higuain, Napoli, 2015-16: finished second in Serie A, nine points back of first

• Dominic Calvert-Lewin, Everton, 2020-21: finished 10th in the Premier League

• Anthony Modeste, Koln, 2015-16: finished fifth in the Bundesliga

• Edinson Cavani, PSG, 2016-17: finished second in Ligue 1, eight points back of first

• Emanuel Emegha, Strasbourg, 2024-25: finished seventh in Ligue 1, qualified for Conference League

So, almost all of these seasons were for mid-table sides — mostly mediocre clubs who had one guy it was worth building the entire attack around. There were two good-not-great Napoli sides. And then, most interestingly, one of the few seasons over the past decade when PSG didn’t win was the one when the highest proportion of their attack was funneled through one player.

Can you win anything with a one-man team?

It seems, then, that there’s a limit on how good a team can be when one player is so responsible for such a large proportion of its shot generation. But the further we go down the list, some more successful sides eventually start to pop up.

The highest xG share for a league-winning team was the 40.1% of Napoli’s xG that went to Victor Osimhen in 2022-23. The highest xG share for a Champions League-winning team was the 39.9% that went to Ronaldo in 2017-18, a year when Real Madrid also finished third in LaLiga. And as for Guardiola-coached teams, the highest xG shares went to Lewandowski in 2015-16 (38.7%) and then to Messi (38%) in 2010-11.

When I ranked the best 25 teams of the past 25 years, that 2015-16 Bayern side landed at No. 20, while 2010-11 Barcelona finished fourth. That Barcelona team is the same one Sir Alex Ferguson called the best team he’s ever faced. It’s also the team that would pop up the most if you asked random soccer fans to name the best team of the past 25 years. They were the apotheosis of a tactics where everyone did everything. But even then, Messi was still responsible for an outsize proportion of their chances on goal.

Not like this, though. Through six games, Haaland is close to doubling Messi’s rate. And there does seem to be a shift that happens the higher you go up the percentage scale. There are a bunch of Messi, Ronaldo, and Lewandowski seasons in the 35 to 38% range, but once you scale beyond 40%, the Champions League- and league-winning teams start to fall away and the midtable, Europa League, and overachieving-but-not-good-enough-to-finish-first sides begin to populate the list.

1:14

Guardiola: Haaland is still above Isak despite Slot claims

Manchester City manager Pep Guardiola believes Erling Haaland is “above” Alexander Isak despite Arne Slot claiming that the Swedish international is the best striker in the world.

Is that because these kinds of players, statistically, can only exist on teams where their teammates aren’t as good as them? If Messi were on, say, Levante, wouldn’t he have landed a lot higher on this list? Or is it because the kind of tactics that leverage a single shooter so heavily put a limit on just how good you can be? What’s harder to defend: A team where you know only one guy is going to shoot, or a team where three different players could score a goal or create a chance?

As Haaland’s goal-scoring burden has grown, his participation in all other aspects of the sport have fallen away. The number of passes he attempts per game has dropped off every season since he arrived in England; currently, he’s playing just 13 passes per game. He’s receiving just three progressive passes per game — the fewest since joining City. And through six matches, he’s attempted one tackle. He did not win the tackle.

When you have one player who is barely doing anything other than shooting the ball from inside the penalty area, you either have to surround him with all of the best players in the world at all of the things other than shooting the ball, or you have to change the way you play. Guardiola’s teams have always pressed high and dominated possession, but you can’t do either of those things when one of your players doesn’t contribute to either of those things.

So, for the first time ever, we’re seeing a Guardiola team that is doing neither of those things. Over his tenure at City, the team has averaged 72.1% of the final-third possession in their matches and allowed 10.45 opposition passes per defensive action (PPDA) in the attacking area of the field. This season, they’re tilting the field at only a 55% rate, and their PPDA has risen to 15.18 — not only the lows (or highs) of the Guardiola era, but seven teams in the league this season have controlled more final-third possession and 16 sides have pressed more aggressively.

City, then, are playing like most of those other one-man teams have played over the past 15 years. But despite having much more talent than those other clubs — or at least investing a lot more money into their players than those other clubs — they’re forcing a much larger proportion of their attack through their one man.

Now, it’s highly unlikely that Haaland continues to generate nearly two-thirds of City’s chance-quality for the rest of the season, but unless there’s another tactical pivot coming, it also seems pretty likely that Haaland, if he stays healthy, does end the season with something close to 40% of City’s expected-goal total for himself. And it’s not impossible that he shatters the 47% mark that Moise Kean set last season.

Someone who has worked with a number of the biggest clubs in the world once told me that he thought all of Guardiola’s tactical innovations throughout the years were just a means of keeping himself interested. He had the talent to keep running it back every season, but what’s the fun in dominating in the exact same way, year after year?

Except, I wonder if it hasn’t become something slightly different. Guardiola has never been able to build a team as good as the one where everyone did everything: that 2010-11 Barcelona team. He’s had many other fantastic and different teams that won, but they all still mostly dominated possession, kept the ball in the final third, and didn’t do it as well as they did in Barcelona. They were all worse versions of the initial prototype, until this year.

This current City side isn’t anywhere close to that Barcelona team on a full-season scale, but with their lack of interest in pressing, their comfort without the ball, and a hyper-speed, battering-ram center forward who only needs to touch the ball 10 times a game to score multiple goals, they do give Guardiola something he’s never had before.

After 15 years, he might finally have a team that could’ve beaten his best team.