Barbara Plett UsherAfrica correspondent

BBC

BBCAhmed Abdul Rahman can hear the thud of artillery from where he lies in a makeshift cluster of tents in the Sudanese city of el-Fasher.

The 13-year-old boy was injured in a recent shelling attack.

“I feel pain in my head and my legs,” he says weakly.

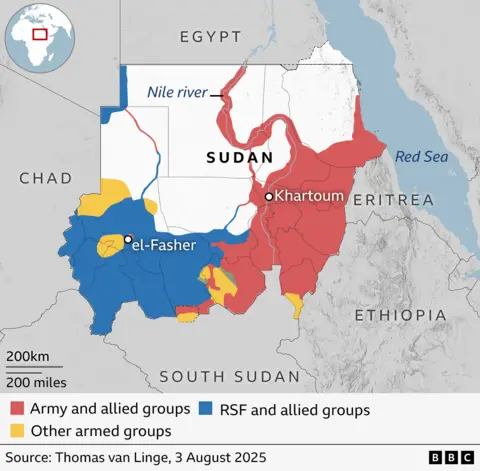

For 17 months the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have besieged el-Fasher, located in their ethnic heartland of Darfur, and now they’re closing in on key military sites in the city.

The conflict in Sudan broke out in 2023 following a power struggle between the top commanders of the RSF and the Sudanese army.

After losing control of the capital Khartoum the paramilitaries have stepped up efforts to seize el-Fasher – the army’s last stronghold in the western Darfur region.

Army-held territory has shrunk to a pocket around the airport. For the tens of thousands of civilians trapped inside the city, each day is a nightmare.

The siege and fighting make it very difficult to get reliable information, but the BBC has worked with freelance journalists inside el-Fasher to get an insight into life for those trapped there.

Warning: This story contains graphic details that some people may find distressing

Ahmed’s “whole body is full of shrapnel”, says his mother Islam Abdullah. “His condition is unstable.”

But with hospitals coming under fire and running out of supplies, medical care is scarce.

She lifts Ahmed’s shirt to reveal his wounds, his bony back a reminder of the hunger stalking the city.

Nearby, Hamida Adam Ali is unable to move, her leg is badly injured. She lay on the road for five days after being hit by shell fire, before she was carried to the camp for people displaced by the conflict.

“I don’t know if my husband is dead or alive,” she says. “My children have been crying for days because there is no food. Sometimes they find something to eat and sometimes they go to bed without food. My leg is rotting – it smells foul now. I am just lying down. I have nothing.”

The RSF have made significant advances in recent weeks. They’ve released footage showing their fighters in a location which the BBC has identified as the headquarters of the military’s armoured corps.

There are other bases nearby that Sudan’s army, including its Sixth Infantry Division, is still defending.

In the past few days, it has posted a video of soldiers said to be cheering the arrival of much-needed supplies, reported to be delivered by airdrops.

But in the media warfare that frames the battles, RSF fighters celebrate what they portray as imminent victory in el-Fasher.

Seizing full control of the city would give them a strategic advantage in the civil war after setbacks earlier this year, easing their access to Libya and strengthening their control over the western border in an arc stretching from South Sudan to parts of Egypt, Sudanese analyst Kholood Khair tells the BBC.

“The RSF would be able to bring in more fuel from southern Libya, more weapons, also from southern Libya, and would be able to safeguard their transit from the border region all the way into Darfur,” she says.

“And from el-Fasher, the RSF would be able to launch attacks into both the Kordofan regions and into the capital [Khartoum] again. And so, it would really position the RSF much more strongly militarily.”

Local armed groups known as the Joint Forces fighting alongside the army also have a lot at stake.

“For the Joint Forces, this is a fight for their homelands,” says Ms Khair. “This is a fight for their ability as armed groups to claim constituencies in Darfur. If they lose Darfur, they effectively no longer have a claim to any part of Darfur… It’s a fight for their political survival.”

The RSF advance is powered by increasingly deadly and sophisticated drones said to be supplied by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), something the wealthy Gulf state denies despite evidence from investigations by war monitors, including UN experts.

Footage verified by the BBC shows drones hitting what looks to be a location near a military site, but also an informal market – civilians are not spared.

Last month more than 75 people were killed in a strike on a mosque during morning prayers, in an attack blamed on the RSF, although it didn’t publicly take responsibility. Rescuers could not find enough funeral shrouds for all the bodies.

Samah Abdullah Hussein says her young son Samir was buried in that mass grave. He had been killed the day before, his brother injured. The shells hit the school yard where they had taken refuge.

“He was hit in the head and the wound was deep, his brain came out,” she says, wiping tears from her eyes. “My other son was hit in the head by shrapnel and in his arm, and I was hit in my right leg.”

Hundreds of thousands have fled el-Fasher over the past year. Those who make it to safety say people were attacked, robbed and killed as they left.

The UN warns of more atrocities if RSF fighters overrun the city.

The paramilitaries deny targeting non-Arab ethnic groups, such as the local Zaghawa community, despite evidence of war crimes presented by the UN and human rights groups. They’re trying to send a different message – with new videos showing them greeting and helping those who flee.

The footage is a jolt for a refugee watching from outside the country, despite its softer tone. He recognizes many of the people stopped by the RSF fighters.

“That last guy we used to play soccer with,” he tells the BBC, “and the one in the middle, he’s a musician, I know him from el-Fasher.”

The refugee also sees some relatives in the group – and asked not to be named in order to protect them.

“It really devastated and shocked me,” he says. “I will be worried until I hear from them, or they send me a message that they are OK, and they’re in a safe place.”

Later that day he sent me word that his family members were safe – a tremendous relief, but a temporary one.

“It’s not just my relatives,” he says. “It’s about all the people that I know. It’s about my memories there. I see every day, people whom I know die, places that I used to go to destroyed. My memories died, not just the people that I know. It’s like a nightmare.”

Many fear what the next weeks might bring. Those still trapped in the city can only wait – and try to survive.

More BBC stories on Sudan civil war:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC